In April 2023, a satellite the size of a microwave was launched into space. The goal: to prepare for asteroid mining. Although the mission, courtesy of a company called AstroForge, encountered problems, it is part of a new wave of potential asteroid miners hoping to make money from cosmic resources.

Potential applications of material from space are plentiful: Asteroids contain metals such as platinum and cobalt, which are used in electronics and batteries for electric vehicles, respectively. Although many of these materials exist on Earth, they may be more concentrated on asteroids than on mountain slopes, making them easier to remove. And scraping in space could reduce the harmful effects of mining on this planet, according to proponents. Proponents of space sources also want to explore the potential of other substances. What if space ice could be used for spacecraft and rocket fuel? Space debris for astronaut housing structures and radiation shielding?

Previous companies have pursued similar goals before, but went bankrupt about half a decade ago. But in the years since that first cohort left the stage, “interest in the field has exploded,” says Angel Abbud-Madrid, director of the Center for Space Resources at the Colorado School of Mines.

Much attention has been focused on the moon, as countries plan to set up outposts there and will need supplies. NASA, for example, has ambitions to build base camps for astronauts within the next decade. China, meanwhile, hopes to establish an international lunar research station.

Still, the allure of space rocks remains powerful and the new crop of companies is hopeful. The economic picture has improved as the cost of rocket launches has declined, as has the regulatory environment, with countries creating laws specifically allowing space mining. But only time will tell whether this decade’s gold miners will capitalize where others have dipped into the red or been buried by their business plans.

An asteroid mining company needs one key ingredient to get started: optimism. The hope that they could start a new industry, one that is out of this world. “Not many people are built to work like this,” says Matt Gialich, co-founder and CEO of AstroForge. Since the company’s demo mission in April 2023, it has not come close to mining.

What he and his colleagues hope to extract, however, are platinum group metals, some of which are used in devices such as catalysts that reduce gas emissions. Substances such as platinum and iridium are now used in electronics. There are also opportunities in green technology and new impetus to produce platinum-based batteries with better storage capacity, which could end up in electric vehicles and energy storage systems.

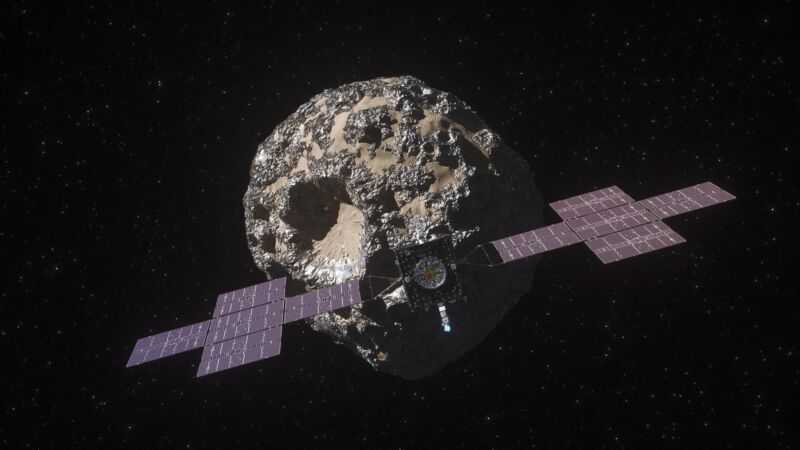

To achieve the company’s goals, AstroForge’s initial mission was loaded with simulated asteroid material and a refinery system designed to extract platinum from the simulant, to demonstrate that metal processing could take place in space.

Things didn’t go exactly as planned. After the small craft entered orbit, it was difficult to identify and communicate with the dozens of other newly launched satellites. The solar panels, which provide power to the spacecraft, would not initially be deployed. And the satellite was initially plagued by a wobble that prevented communication. They were unable to perform the simulated extraction.

The company will soon embark on a second mission, with a different goal: to shoot at an asteroid and take a photo — a surveying project that could help the company understand what valuable materials are on a given asteroid.

Another company called TransAstra sells a telescope and software designed to detect objects such as asteroids moving through the sky; The Chinese company Origin Space has a satellite for observing asteroids in orbit around the Earth and is testing its technology relevant to mining there. Meanwhile, Colorado company Karman+ plans to go directly to an asteroid in 2026 and test out digging equipment.

To achieve the ultimate goal of extracting metals from space rocks, TransAstra, Karman+ and AstroForge have collectively received tens of millions of dollars in venture capital funding to date.

Another company with similar objectives, simply Asteroid Mining Corporation Ltd. mentioned, does not want to be much dependent on external investments in the long term. This dependence has actually contributed to previous companies going bankrupt. Instead, founder and CEO Mitch Hunter-Scullion is focusing his company’s early work on terrestrial applications that will pay off immediately, so he can fund future work in the broader universe. In 2021, the company collaborated with the Tohoku University Space Robotics Laboratory, located in Japan, to work on space robots.

Together they built a six-legged robot called the Space Capable Asteroid Robotic Explorer, or SCAR-E. Designed to operate in microgravity, it can crawl over a rough surface and collect data and sample what’s there. In 2026, the company plans to conduct a demonstration mission to analyze soil on the moon.

For now, however, SCAR-E remains on Earth and inspects ship hulls. According to one market research platform, this is a nearly $13 billion market globally – compared to the asteroid mining market, which currently costs $0 as no one has mined an asteroid yet.

Such grounded work can provide the company with a revenue stream before and during their time in space. “I think every asteroid mining company has the realization that money is running out, investors are getting tired and you have to do something,” Hunter-Scullion says.

“My view is that unless you’ve built something that makes sense on Earth,” he added, “you’ll never be able to mine an asteroid.”